Ilya Rice: How I Won the Enterprise RAG Challenge

From Zero to SoTA in a Single Competition

In this guest blog post Ilya Rice describes the approach that helped him build the best RAG and win in the Enterprise RAG Challenge. He took first place in both prize categories and on SotA leaderboard. Source code.

Also posted at TimeToAct Austria and on Habr (RU).

What is the RAG Challenge about?

The task was to create a question-answering system based on annual company reports. Briefly, the process on the competition day was as follows:

- You're given 100 annual reports from randomly selected companies and 2.5 hours to parse them and build a database. The reports are PDFs, each up to 1000 pages long.

- Then, 100 random questions are generated (based on predefined templates), which your system must answer as quickly as possible.

All questions must have definitive answers, such as:

- Yes/No;

- Company name (or multiple company names in some cases);

- Titles of leadership positions, launched products;

- Numeric metrics: revenue, store count, etc.

Each answer must include references to pages containing evidence of the response, ensuring the system genuinely derived the answer rather than hallucinating.

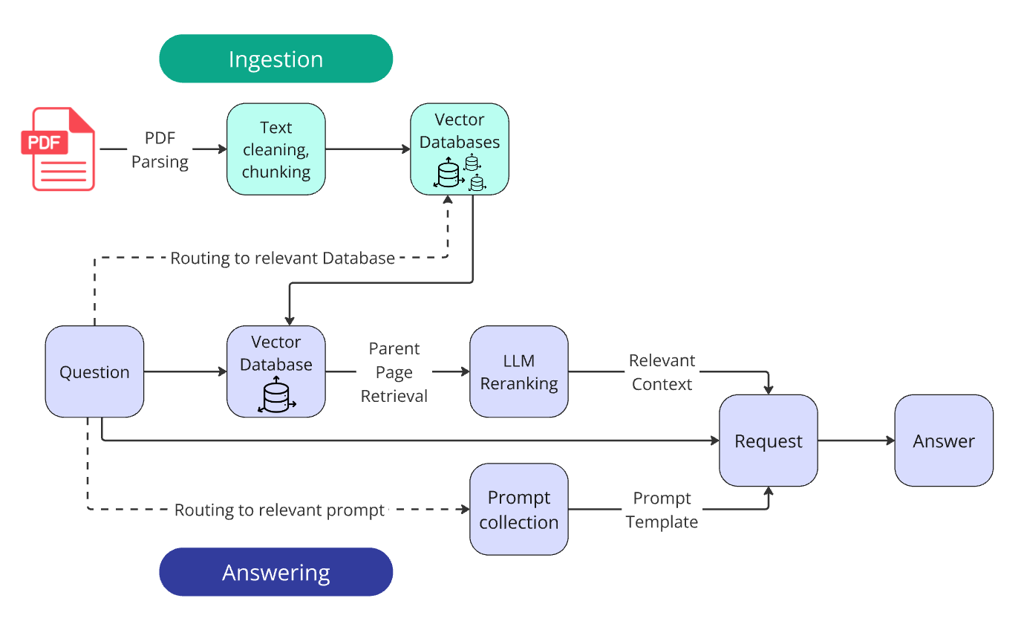

Winning system architecture:

Apart from basic steps, the winning solution incorporates two routers and LLM reranking.

You can check out the questions and answers produced by my best-performing system here.

Now, I'll delve into every step involved in building the system, the bumps and bruises I experienced along the way, and the best practices discovered during this process.

Quick Guide to RAG

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is a method that extends the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) by integrating them with a knowledge base of any size.

Development pathway of a basic RAG system includes the following stages:

- Parsing: Preparing data for the knowledge base by collecting documents, converting them to text format, and cleaning out irrelevant noise.

- Ingestion: Creating and populating the knowledge base.

- Retrieval: Building a tool that finds and returns relevant data based on user queries, typically employing semantic search within a vector database.

- Answering: Enriching the user's prompt with retrieved data, sending it to the LLM, and returning the final answer.

1. Parsing

To start populating any database, PDF documents must first be converted to plain text. PDF parsing is an extremely non-trivial task filled with countless subtle difficulties:

- preserving table structures;

- retaining critical formatting elements (e.g., headings and bullet lists);

- recognizing multi-column text;

- handling charts, images, formulas, headers/footers, and so on.

Interesting PDF parsing issues I encountered (but didn't have time to solve):

- Large tables are sometimes rotated by 90 degrees, causing parsers to produce garbled and unreadable text.

- Charts composed partially of images and partially of text layers.

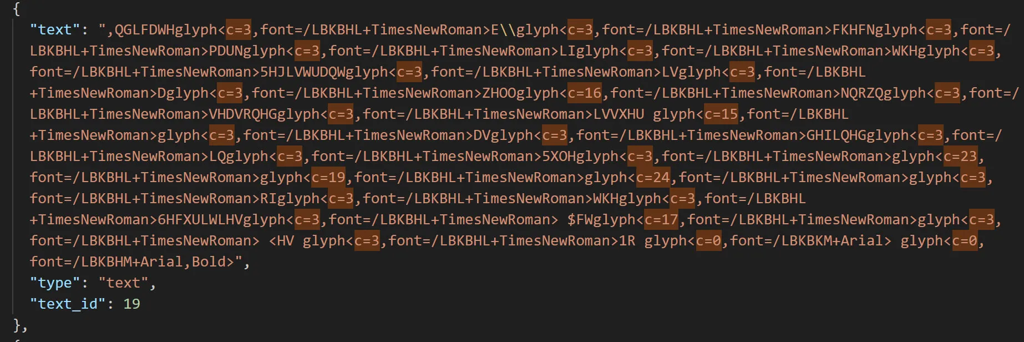

- Some documents had font encoding issues: visually, the text looks fine, but attempting to copy or parse it results in a nonsensical set of characters.

Fun fact: I investigated this issue separately and discovered that the text could be decoded—it was a Caesar cipher with varying ASCII shifts per word. This raised numerous questions for me. If someone intentionally encrypted copying of a publicly available company report—why? If the font broke during conversion—why precisely this way?

Choosing a Parser

I experimented with about two dozen PDF parsers:

- niche parsers;

- reputable ones;

- cutting-edge ML-trained parsers;

- proprietary parsers with API access.

I can confidently state that currently, no parser can handle all nuances and fully return PDF content as text without losing part of the important information along the way.

The best-performing parser for the RAG Challenge turned out to be the relatively known Docling. Interestingly, one of the competition organizers—IBM—is behind its development.

Parser Customization

Despite its excellent results, Docling lacked some essential capabilities. These features existed partially but in separate configurations that couldn't be combined into one.

Therefore, I rolled up my sleeves, thoroughly examined the library's source code, and rewrote several methods to fit my needs, obtaining a JSON containing all necessary metadata after parsing. Using this JSON, I constructed a Markdown document with corrected formatting and near-perfect conversion of table structures from PDF to not just MD, but also HTML format, which proved important later on.

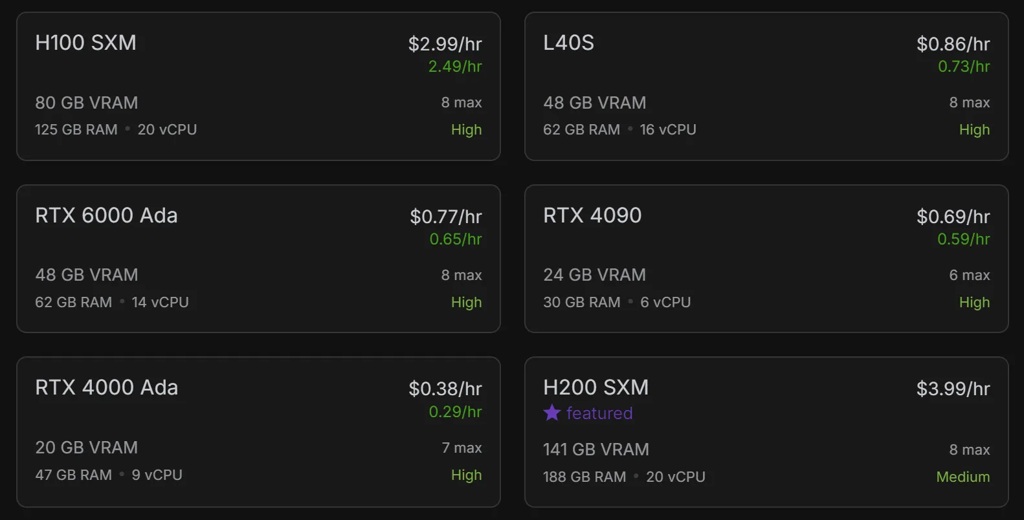

This library is quite fast but still not enough to parse 15 thousand pages within 2.5 hours on a personal laptop. To solve this, I leveraged GPU acceleration for parsing and rented a virtual machine with a 4090 GPU for 70 cents an hour for the competition.

Runpod turned out to be extremely convenient for short-term GPU rentals

Runpod turned out to be extremely convenient for short-term GPU rentals

Parsing all 100 documents took about 40 minutes, which, based on reports and comments from other participants, is an extremely high parsing speed.

At this stage, we have reports parsed into JSON format.

Can we now populate the database?

Not yet. First, we must clean the text from noise and preprocess the tables.

Text Cleaning and Table Preparation

Sometimes parts of the text get parsed incorrectly from PDFs and contain specific syntax, reducing readability and meaningfulness. I addressed this using a batch of dozen regular expressions.

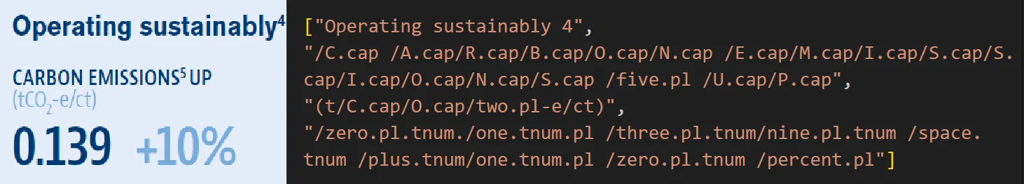

Example of poorly parsed text

Example of poorly parsed text

Documents with the aforementioned Caesar cipher were also detected via regex patterns. I tried to decode them, but even after restoration, they contained many artifacts. Therefore, I simply ran these documents entirely through OCR.

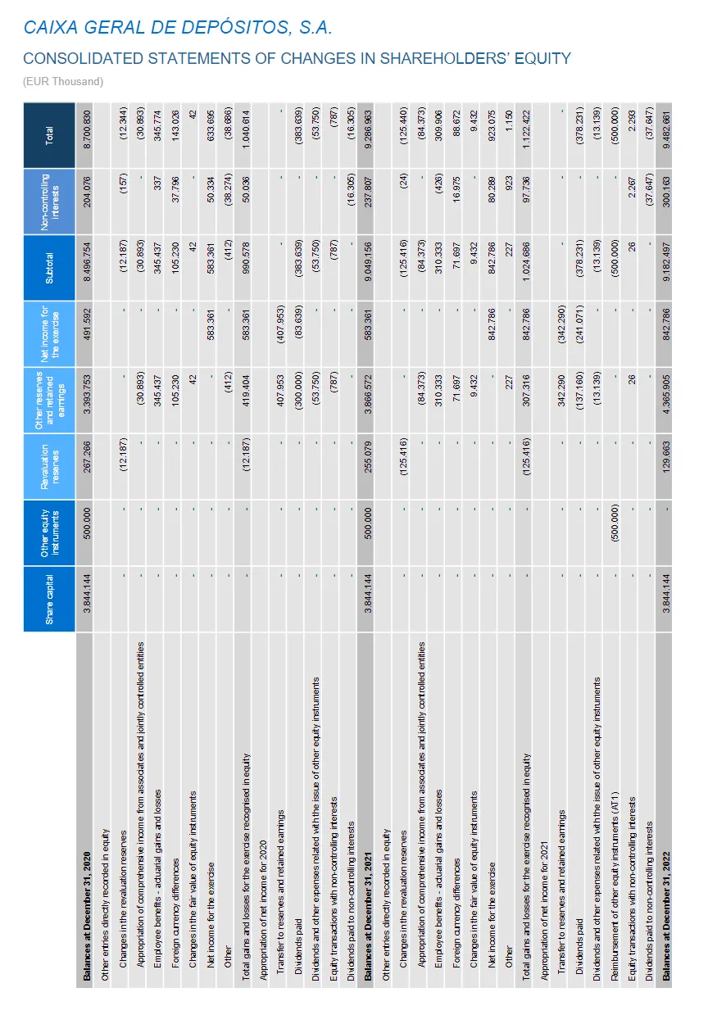

Table Serialization

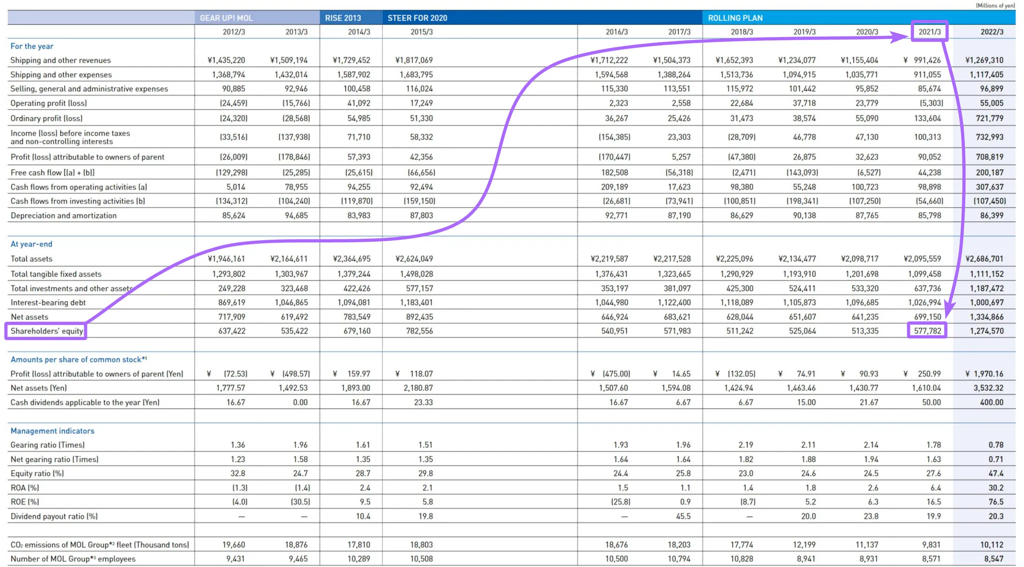

In large tables, the metric name (horizontal header) is often positioned too far from vertical headers, weakening semantic coherence.

There are 1,500 irrelevant tokens separating vertical and horizontal headers

There are 1,500 irrelevant tokens separating vertical and horizontal headers

This significantly reduces the chunk's relevance in vector search (let alone situations where the table doesn't fit entirely into one chunk). Additionally, LLMs struggle to match metric names with headers in large tables, possibly returning a wrong value.

Serialization of tables became the solution. Research on this topic is sparse, so I had to navigate this independently. You can google Row-wise Serialization, Attribute-Value Pairing, or read this research paper.

The essence of serialization is transforming a large table into a set of small, contextually independent strings.

After extensive experiments with prompts and Structured Output schemas, I found a solution that enabled even GPT-4o-mini to serialize huge tables almost losslessly. Initially, I fed tables to the LLM in Markdown format, but then switched to HTML format (this is where it proved useful!). Language models understand it much better, plus it allows describing tables with merged cells, subheadings, and other structural complexities.

To answer a question like, "What was the company's shareholder's equity in 2021?" it's sufficient to feed the LLM a single sentence rather than a large structure with lots of "noise."

During serialization, the whole table is converted into a set of such independent blocks:

subject_core_entity: Shareholders' equityinformation_block: Shareholders' equity for the years from 2012/3 to 2022/3 are as follows: ¥637,422 million (2012/3), ¥535,422 million (2013/3), ¥679,160 million (2014/3), ¥782,556 million (2015/3), ¥540,951 million (2016/3), ¥571,983 million (2017/3), ¥511,242 million (2018/3), ¥525,064 million (2019/3), ¥513,335 million (2020/3), ¥577,782 million (2021/3), and ¥1,274,570 million (2022/3).

After obtaining a serialized version of the table, I placed it beneath the original table as a kind of textual annotation for each element.

You can view the serialization prompt and logic in the project's repository: tables_serialization.py

*Despite serialization's fantastic potential, the winning solution ultimately didn't use it. I'll explain why at the end of the article.

2. Ingestion

Reports have been converted from PDF to clean Markdown text. Now let's create databases from them.

Agreeing on terminology

In the realm of search systems (Google Search, full-text-search, Elastic Search, vector search, etc.), a document is a single indexed element returned by the system as a query result. A document could be a sentence, paragraph, page, website, image—doesn't matter. But personally, this definition always confuses me due to the more common, everyday meaning: a document as a report, contract, or certificate.

Therefore, from here on, I'll use document in its everyday meaning.

The element stored in the database, I'll call a chunk, since we store simply sliced pieces of text.

Chunking

According to the competition rules, we had to specify the pages containing relevant information. Enterprise systems use the same approach: references allow verifying that the model's answer isn't hallucinated.

This not only makes the system more transparent to users but also simplifies debugging during development.

The simplest option is to use a whole page of a document as a chunk since pages rarely exceed a couple thousand tokens (although table serialization could expand a page up to five thousand).

But let's think again about the semantic coherence between the query and a chunk of document text. Usually, an informational piece sufficient for an answer is no larger than ten sentences.

Thus, logically, a target statement within a small paragraph will yield a higher similarity score than the same statement diluted within a whole page of weakly relevant text.

I split the text on each page into chunks of 300 tokens (approximately 15 sentences).

To slice the text, I used a recursive splitter with a custom MD dictionary. To avoid losing information cut between two chunks, I added a small text overlap (50 tokens).

If you're worried that overlap won't fully eliminate risks from poor slicing, you can Google "Semantic splitter." This is especially important if you plan to insert only found chunks in the context.

However, the precision of slicing had almost no effect on my retrieval system.

Each chunk stores its ID and the parent page number in its metadata.

Vectorization

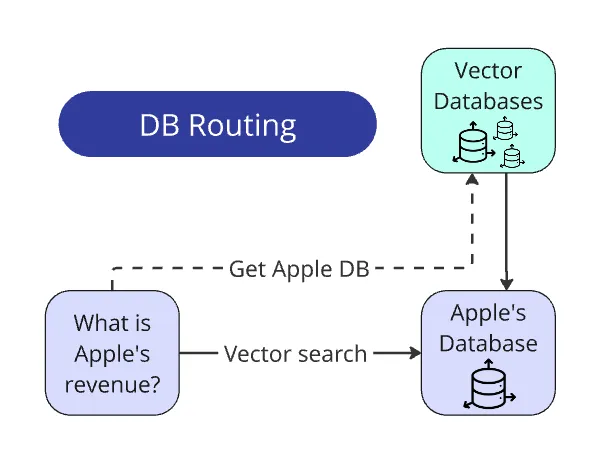

Our collection of chunks is prepared; now let's create the vector database—or rather, databases. 100 databases, where 1 database = 1 document.

Because why mix information from all companies into one heap and later try to separate one company's revenue from another's? Target information for an answer is always strictly within a single document.

We only need to determine which database to query for a given question (more on that later).

To create, store, and search the vector databases, I used FAISS.

A bit about vector database formats

Databases were created with the IndexFlatIP method.

The advantage of Flat indices is that all vectors are stored "as-is," without compression or quantization. Searches use brute-force, giving higher precision. The downside is such searches are significantly more compute- and memory-intensive.

If your database has at least a hundred thousand elements, consider IVFFlat or HNSW. These formats are much faster (though require a bit more resources when creating the database). But increased speed comes at the cost of accuracy due to approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search.

Separating chunks of all documents into different indexes allowed me to use Flat databases.

IP (inner product) is used to calculate the relevance score through cosine similarity. Aside from IP, there's also L2—which calculates relevance score via Euclidean distance. IP typically gives better relevance scoring.

To embed chunks and queries into vector representation, I used text-embedding-3-large.

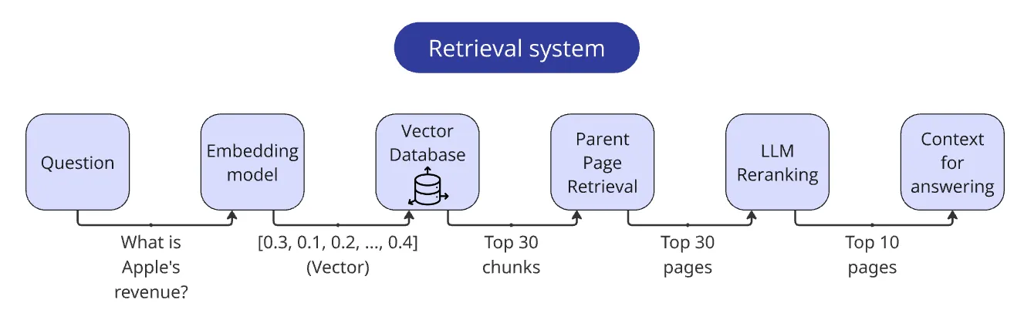

3. Retrieval

After creating our databases, it's time to move on to the "R" (Retrieval) part of our RAG system.

A Retriever is a general search system that takes a query as input and returns relevant text containing the information necessary for an answer.

In the basic implementation, it is simply a query to a vector database, extracting the top_n results.

This is an especially critical part of the RAG system: if the LLM does not receive the necessary information in the context of a query, it cannot provide a correct answer—no matter how well you fine-tune your parsing or answer prompts.

Junk in → Junk out.

The quality of a retriever can be improved in many ways. Here are methods I explored during the competition:

Hybrid search: vDB + BM25

Hybrid search combines semantic vector-based search with traditional keyword-based text search (BestMatch25). It theoretically improves retrieval accuracy by not only considering the meaning of the text but also precise keyword matches. Typically, results from both methods are merged and reranked by a combined score.

I didn't particularly like this approach: in its minimal implementation, it often reduced the retrieval quality instead of improving it.

Generally, hybrid search is a good technique and can be refined further by modifying input queries. At its simplest, LLMs can rephrase questions to remove noise and increase keyword density.

If you've had positive experiences with hybrid search, especially regarding potential issues and solutions, please share in the comments.

In any case, I had more promising alternatives in mind and decided not to explore this direction further.

Cross-encoder reranking

Reranking the results of vector search using Cross-encoder models seemed promising. In short, Cross-encoders give a more precise similarity score but are slower.

Cross-encoders lie between embedding models (bi-encoders) and LLMs. Unlike comparing texts via their vector representations (which inherently lose some information), cross-encoders directly assess semantic similarity between two texts, giving more accurate scores.

However, pairwise comparisons of the query with every database element take too long.

Thus, cross-encoder reranking is suitable only for a small set of chunks already filtered by vector search.

At the last minute, I abandoned this method due to the scarcity of cross-encoder reranking models available via APIs. Neither OpenAI nor other large providers offered them, and I didn't want the hassle of managing another API balance.

But if you're interested in trying cross-encoder reranking, I recommend Jina Reranker. It performs well on benchmarks, and Jina offers a generous number of requests upon registration.

Ultimately, I opted for an even more attractive alternative: LLM reranking!

LLM reranking

Simple enough: pass text and a question to the LLM and ask, “Is this text helpful for answering the question? How helpful? Rate its relevance from 0 to 1.”

Until recently, this approach wasn't viable due to the high cost of powerful LLM models. But now we have fast, cheap, and smart enough LLMs available.

Like Cross-encoder reranking, we apply this after initial filtering via vector search.

I developed a detailed prompt describing general guidelines and explicit relevance criteria in increments of 0.1:

- 0 = Completely Irrelevant: The block has no connection or relation to the query.

- 0.1 = Virtually Irrelevant: Only a very slight or vague connection to the query.

- 0.2 = Very Slightly Relevant: Contains an extremely minimal or tangential connection.

- ...

The LLM query is formatted as Structured output with two fields: reasoning (allowing the model to explain its judgment) and relevance_score, allowing extraction directly from the JSON without additional parsing.

I further optimized the process by sending three pages at once in one request, prompting the LLM to return three scores simultaneously. This increased speed, reduced cost, and slightly improved scoring consistency, as adjacent blocks of text grounded the model's assessments.

The corrected relevance score was calculated using a weighted average:

vector_weight = 0.3, llm_weight = 0.7

In theory, you could bypass vector search and pass every page through the LLM directly. Some participants did just that, successfully. However, I believe a cheaper, faster filter using embeddings is still necessary. For a 1000-page document (and some documents were this large), answering just one question would cost roughly 25 cents—too expensive.

And, after all, we’re competing in a RAG challenge, aren’t we?

Reranking via GPT-4o-mini cost me less than one cent per question! This approach delivered excellent quality, speed, and cost balance—exactly why I chose it.

Check out the reranking prompt here.

Parent Page Retrieval

Remember how I talked about splitting text into smaller chunks? Well, there's a small but important caveat here.

Yes, the core information needed to answer is usually concentrated in a small chunk — which is exactly why breaking the text into smaller pieces improves retrieval quality.

But the rest of the text on that page may still contain secondary — yet still important — details.

Because of this, after finding the top_n relevant chunks, I only use them as pointers to the full page, which then goes into the context. That's precisely why I recorded the page number in each chunk's metadata.

Assembled Retriever

Let's recap the final retriever steps:

- Vectorize the query.

- Find the top 30 relevant chunks based on the query vector.

- Extract pages via chunk metadata (remember to deduplicate!).

- Pass pages through the LLM reranker.

- Adjust relevance scores for pages.

- Return top 10 pages, prepend each page with its number, and merge them into a single string.

Our retriever is now ready!

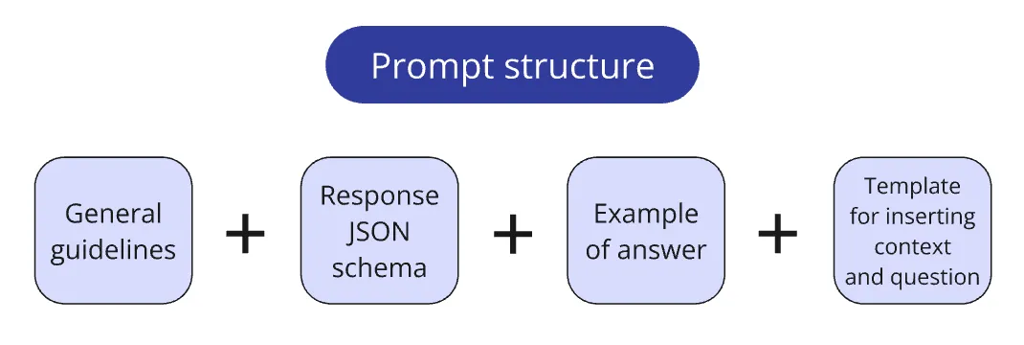

4. Augmentation

Our vector database is set up, and the retriever is ready. With the "R" (Retrieval) part of RAG behind us, we now approach the "A" (Augmentation) part, which is pretty straightforward, consisting mainly of f-strings and concatenations.

One interesting detail is how I structured prompt storage. After trying different approaches across multiple projects, I eventually settled on the following approach:

I store prompts in a dedicated prompts.py file, typically splitting prompts into logical blocks:

- Core system instruction;

- Pydantic schema defining the response format expected from the LLM;

- Example question-answer pairs for creating one-shot/few-shot prompts;

- Template for inserting the context and the query.

A small function combines these blocks into the final prompt configuration as needed. This method allows flexible testing of different prompt configurations (e.g., comparing the effectiveness of different examples for one-shot prompts).

Some instructions may repeat across multiple prompts. Previously, changing such instructions meant synchronizing updates across all prompts using them, easily leading to mistakes. The modular approach solved this issue. Now, I place recurring instructions into a shared block and reuse it across several prompts.

Additionally, modular blocks simplify handling when prompts become overly long.

All prompts can be viewed in the project repository: prompts.py

5. Generation

The third part "G" in RAG is the most labor-intensive. Achieving high quality here requires skillful implementation of several fundamental techniques.

Routing queries to the database

This is one of the simplest yet most useful parts of a RAG system.

Recall that each report has its own separate vector database. The question generator was designed so that the company's name always explicitly appears in the question.

We also have a list of all company names (provided along with the PDF reports at the start of the competition). Thus, extracting the company's name from a query doesn't even require an LLM: we simply iterate over the list, extract the name via re.search() from the question, and match it to the appropriate database.

In real-world scenarios, routing queries to databases is more complex than in our controlled, sterile conditions. Most likely, you'll have additional preliminary tasks: tagging databases or using an LLM to extract entities from the question to match them to a database.

But conceptually, the approach remains unchanged.

To summarize:

Found the name → matched to DB → search only in this DB. The search space shrinks 100-fold.

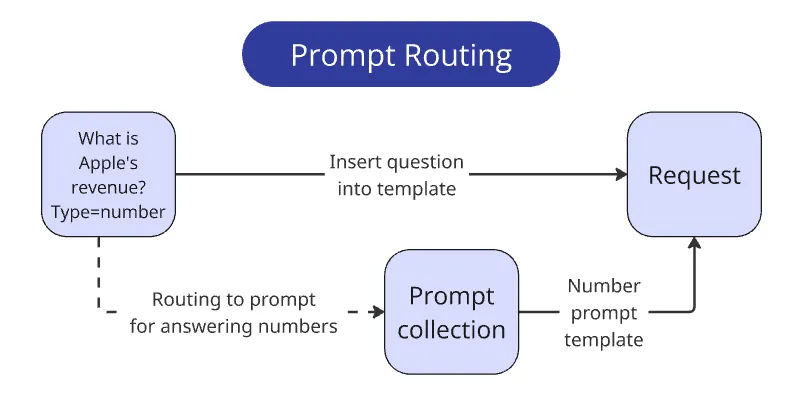

Routing queries to prompts

One requirement of the competition was the answer format. Each answer must be concise and strictly conform to the data type as if storing it directly into the company's database.

Alongside each question, the expected type is given explicitly—int/float, bool, str, or list[str].

Each type involves 3–6 nuances to consider when responding.

For example, if a question asks for a metric value, the answer must be solely numeric, without comments, currency signs, etc. For monetary metrics, the currency in the report must match the currency in the question, and numbers must be normalized—reports often write something like "$1352 (in thousands)" and the system must reply with "1352000".

How to ensure the LLM considers all these nuances simultaneously without making errors? Simply put: you can't. The more rules you give the LLM, the higher the chance it'll ignore them. Even eight rules are dangerously many for current LLMs. A model's cognitive capacity is limited, and additional rules distract it from the main task—answering the posed question.

This logically leads to the conclusion that we should minimize the number of rules per query. One approach is to break a single query into a sequence of simpler ones.

In our case, though, we can achieve an even simpler solution—since the expected response type is explicitly provided, we only supply the relevant instruction set to the prompt, depending on the answer type.

I wrote four prompt variations and chose the correct one with a simple if else.

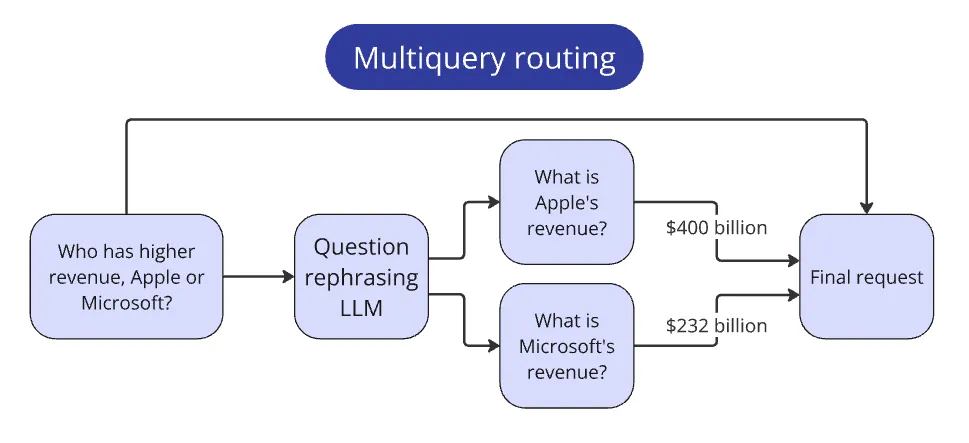

Routing compound queries

The competition included questions comparing metrics from multiple companies. Such questions didn't fit the paradigm of other simpler queries, as they required additional steps to answer.

Example question:

Who has higher revenue, Apple or Microsoft?

Let's think: how would a human approach this task?

First, they'd find each company's revenue separately, then compare them.

We embed the same behavior into our system.

We pass the initial comparison question to the LLM and ask it to create simpler sub-questions that extract metrics for each company individually.

In our example, the simpler sub-questions would be:

What is Apple's revenue? and What is Microsoft's revenue?

Now we can process these simpler queries through the standard pipeline for each company separately.

After gathering answers for each company, we pass them into the context to answer the original question.

This pattern applies to any complex queries. The key is recognizing them and identifying the necessary sub-steps.

Chain of Thoughts

CoT significantly improves answer quality by making the model "think aloud" before providing the final response. Rather than giving an immediate answer, the LLM generates a sequence of intermediate reasoning steps leading to the solution.

Just like humans, LLMs handle complex problems better when breaking them down into smaller, simpler ones. CoT helps the model avoid missing crucial details, methodically process information, and reach correct conclusions. It's especially useful when context includes "traps" that might lead the model astray.

You've undoubtedly heard the iconic phrase, Think step by step. This was one of the earliest attempts to enhance answer quality through prompting. It practically gave rise to fancy "prompt engineering." However, for serious tasks, such generic instructions aren't sufficient.

LLMs can sometimes "fake" reasoning—for instance, giving an immediate answer and then retroactively justifying it or hallucinating non-existent facts. This issue is particularly common among weaker models like GPT-4o-mini or Llama 8b.

To ensure CoT is beneficial, you must clearly guide the model on how to reason. Explain reasoning steps, objectives, and provide examples.

Structuring reasoning steps explicitly according to the prompt instructions can significantly enhance rule-following.

In RAG, when reports lack the exact requested metric, the context may include similar but non-identical information. Models might attempt to twist the provided data to fit the requested metric. Because models are trained to be helpful, they are biased toward providing some answer rather than admitting ignorance.

Trying to counteract this bias by just asking the model to be skeptical does work — but not consistently and not in all cases. Instead, prompting the model explicitly to analyze information from different angles or perspectives helps much more.

I specifically instructed the model to focus on assessing the compatibility of metrics between questions and context. This significantly reduced hallucinations.

Example reasoning with ambiguous context:

Question:

What is the Research and development equipment, at cost, for Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Inc.?

Model's reasoning steps:

- The question asks for 'Research and development equipment, at cost' for Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Inc. This indicates a specific value from the balance sheet, representing the original purchase price of equipment specifically used for R&D, without any accumulated depreciation.

- The context (page 35) shows 'Property and equipment, net' at $12,500. This is a net value (after depreciation), and it's a broader category, encompassing all property and equipment, not just R&D equipment.

- The context (page 37) also mentions 'Accumulated Depreciation' of $110,000 for 'Machinery and Equipment'. This represents the total depreciation, not the original cost, and, importantly, it doesn't specify that this equipment is exclusively for R&D.

- Neither of these metrics exactly matches the requested metric. 'Property and equipment, net' is too broad and represents the depreciated value. 'Accumulated Depreciation' only shows depreciation, not cost, and lacks R&D specificity.

- Since the context doesn't provide the original cost of only R&D equipment, and we cannot make assumptions, perform calculations, or combine information, the answer is 'N/A'.

Structured outputs

Structured Output (SO) is a way of forcing the model to respond in a strictly defined format. It's usually passed as a separate parameter to the API, such as a Pydantic or JSON schema.

This guarantees that the model always returns valid JSON strictly adhering to the provided schema.

Field descriptions can also be included in the response schema. These don't affect structure but are treated by the LLM as part of the prompt.

For example, here's a Pydantic schema for LLM reranking:

class RetrievalRankingSingleBlock(BaseModel):

"""Rank retrieved text block relevance to a query."""

reasoning: str = Field(

description=(

"Analysis of the block, identifying key information and how it "

"relates to the query"

)

)

relevance_score: float = Field(

description=(

"Relevance score from 0 to 1, where 0 is Completely Irrelevant "

"and 1 is Perfectly Relevant"

)

)

With this schema, the LLM always returns a JSON with two fields—the first a string, the second a number.

CoT SO

The methods described above are ideally combined with each other.

During generation, the model has a dedicated field specifically for reasoning and a separate field for the final answer. This allows us to extract the answer without needing to parse it from lengthy reasoning steps.

Chain of Thought can be implemented within Structured Outputs in several ways. For example, you could use multiple JSON fields, each guiding the model to intermediate conclusions whose combination leads it to the correct final answer.

However, because the logic required for answering competition questions couldn't be described by a single predefined set of step-by-step instructions, I employed a more general approach, providing the model with a single reasoning field and defining the reasoning sequence directly within the prompt.

In my main schema for answering competition questions, there were just four fields:

- step_by_step_analysis — preliminary reasoning (the Chain of Thought itself).

- reasoning_summary — a condensed summary of the previous field (for easier tracking of the model’s logic).

- relevant_pages — report page numbers referenced by the answer.

- final_answer — a concise answer formatted as required by the competition.

The first three fields were reused across all four prompts tailored for different answer types. The fourth field varied each time, specifying the answer type and describing particular nuances the model had to consider.

For example, ensuring that the final_answer field would always be a number or "N/A" was done like this:

final_answer: Union[float, int, Literal['N/A']]

SO Reparser

Not all LLMs support Structured Outputs, which guarantee full adherence to schemas.

If a model doesn’t have a dedicated Structured Output feature, you can still present the output schema directly within the prompt. Models are usually smart enough to return valid JSON in most cases. However, a portion of answers will inevitably deviate from the schema, breaking the code. Smaller models, in particular, fail to conform about half the time.

To address this, I wrote a fallback method that validates the model’s response against the schema using schema.model_validate(answer). If validation fails, the method sends the response back to the LLM, prompting it to conform to the schema.

This method brought schema compliance back up to 100%, even for the 8b model.

Here's the prompt itself.

One-shot Prompts

This is another common and fairly obvious approach: adding an example answer pair to the prompt improves response quality and consistency.

I added a "question → answer" pair to each prompt, writing the answer in the JSON format defined by Structured Outputs.

The example serves multiple purposes simultaneously:

- Demonstrates an exemplary step-by-step reasoning process.

- Further clarifies correct behavior in challenging cases (helping recalibrate the model's biases).

- Illustrates the JSON structure that the model’s answer should follow (particularly useful for models lacking native SO support).

I paid significant attention to crafting these example answers. The quality of examples in the prompt can either boost or diminish response quality, so each example must be perfectly consistent with the directives and nearly flawless overall. If an example answer contradicts instructions, the model becomes confused, which can negatively affect performance.

I meticulously refined the step-by-step reasoning field in the examples, manually adjusting the reasoning structure and wording of each phrase.

Instruction Refinement

This part is comparable in labor-intensity to the entire data preparation stage due to endless iterative debugging, proofreading of answers, and manual analysis of the model's reasoning process.

Analyzing Questions

Before writing prompts, I thoroughly studied both the response requirements and the question generator.

The key to a good system with an LLM under the hood is understanding customer needs. Typically, this involves deep immersion into a professional domain and meticulous examination of questions. I'm convinced it's impossible to create a truly high-quality QA system for businesses unless you clearly understand the questions themselves and how to find answers (I'd be glad if someone could convince me otherwise).

This understanding is also required to clarify all implicit meanings arising from user questions.

Let's consider the example question Who is the CEO of ACME inc?

In an ideal world, a report would always explicitly provide the answer, leaving no room for misinterpretation:

CEO responsibilities are held by John Doe

A RAG system would locate this sentence in the report, add it to the query context, and the user would receive an unambiguous answer: John Doe

However, we live in the real world, where tens of thousands of companies express information in unlimited variations, with numerous additional nuances.

This raises the question: what exactly can fall under the term "CEO"?

- How literally should the system interpret the client's question?

- Does the client want to know the name of the person holding a similar managerial role, or strictly that specific job title?

- Is stepping slightly away from a literal interpretation acceptable? How far is too far?

Potentially, the following positions could be included:

- Chief Executive Officer — obviously, just the abbreviation spelled out.

- Managing Director (MD), President, Executive Director — slightly less obvious. Different countries use different titles for this role (MD in the UK and Europe, President in America and Japan, Executive Director in the UK, Asian countries, and non-profits).

- Chief Operating Officer, Principal Executive Officer, General Manager, Administrative Officer, Representative Director — even less obvious. Depending on the country and company structure, there may not be a direct CEO equivalent; these roles, although closest to CEO, have varying levels of overlap in responsibilities and authority—from 90% down to 50%.

I'm unsure if there's an existing term for this, but personally, I refer to this as the "interpretation freedom threshold" issue.

When responses are free-form, the interpretation freedom threshold is resolved relatively easily. In ambiguous cases, LLM tries to encompass all implicit meanings from the user's query, adding several clarifications.

Here's a real example of a ChatGPT response:

Based on the provided context, Ethan Caldwell is the Managing Director, which is the closest equivalent to a CEO in this company. However, he has been formally suspended from active executive duties due to an ongoing regulatory investigation. While he retains the title, he is not currently involved in company operations, and leadership has been temporarily transferred to the senior management team under board supervision.

However, if the system architecture requires concise answers, as in the RAG Challenge, the model behaves unpredictably in these situations, relying on its internal “intuition”.

Thus, the interpretation freedom threshold must be defined and calibrated in advance. But since it's not possible to define and quantify this threshold explicitly, all major edge cases must be identified, general query interpretation rules formulated, and ambiguities clarified with the customer.

Beyond interpretation issues, general dilemmas may also occur.

For example: Did ACME inc announce any changes to its dividend policy?

Should the system interpret the absence of information in the report as an indication that no changes have been announced?

Rinat (the competition organizer) can confirm—I bombarded him with dozens of similar questions and dilemmas during competition preparation :)

Prompt Creation

One week before the competition started, the question generator’s code was made publicly available. I immediately generated a hundred questions and created a validation set from them.

Answering questions manually is quite tedious, but it helped me in two key areas:

- The validation set objectively measures the system's quality as I make improvements. By running the system on this set, I monitored how many questions it answered correctly and where it most commonly made mistakes. This feedback loop aids iterative improvements of prompts and other pipeline components.

- Manually analyzing questions highlighted non-obvious details and ambiguities in questions and reports. This allowed me to clarify response requirements with Rinat and unambiguously reflect these rules in the prompts.

I incorporated all these clarifications into prompts as directive sets.

Directive examples:

Answer type = Number

Return 'N/A' if metric provided is in a different currency than mentioned in the question. Return 'N/A' if metric is not directly stated in context EVEN IF it could be calculated from other metrics in the context. Pay special attention to any mentions in the context about whether metrics are reported in units, thousands, or millions, to adjust the number in final answer with no changes, three zeroes or six zeroes accordingly. Pay attention if the value is wrapped in parentheses; it means the value is negative.

Answer type = Names

If the question asks about positions (e.g., changes in positions), return ONLY position titles, WITHOUTnames or any additional information. Appointments to new leadership positions also should be counted as changes in positions. If several changes related to a position with the same title are mentioned, return the title of such position only once. Position title always should be in singular form.

If the question asks about newly launched products, return ONLY the product names exactly as they are in the context. Candidates for new products or products in the testing phase are not counted as newly launched products.

The model easily followed certain directives, resisted others due to skewed biases, and struggled with some, causing errors.

For example, the model repeatedly stumbled when tracking measurement units (thousands, millions), forgetting to append necessary zeroes to the final answer. So, I supplemented the directive with a brief example:

Example for numbers in thousands:

Value from context:

4970,5 (in thousands $)Final answer:

4970500

Eventually, I developed prompts for each question format and several auxiliary prompts:

- Final prompt for Number-type questions

- Final prompt for Name-type questions

- Final prompt for Names-type questions

- Final prompt for Boolean-type questions

- Final prompt for Comparative-type questions (to compare answers from multiple companies via multi-query routing)

- Paraphrasing prompt for Comparative-type questions (to initially find metrics in reports)

- LLM reranking prompt

- SO Reparser prompt

Meticulous refinement of instructions combined with one-shot and SO CoT resulted in significant benefits. The final prompts entirely recalibrated unwanted biases in the system and greatly improved attentiveness to nuances, even for weaker models.

System Speed

Initially, the RAG Challenge rules were stricter, requiring the system to answer all 100 questions within 10 minutes to be eligible for a monetary prize. I took this requirement seriously and aimed to fully leverage OpenAI's Tokens Per Minute rate limits.

Even at Tier 2, the limits are generous—2 million tokens/minute for GPT-4o-mini and 450k tokens/minute for GPT-4o. I estimated the token consumption per question and processed questions in batches of 25. The system completed all 100 questions in just 2 minutes.

In the end, the time limit for submitting solutions was significantly extended — the other participants simply couldn't make it in time :)

System Quality

Having a validation set helped improve more than just prompts—it benefited the entire system.

I made all key features configurable, allowing me to measure their real-world impact and fine-tune hyperparameters. Here are some example config fields:

class RunConfig:

use_serialized_tables: bool = False

parent_document_retrieval: bool = False

use_vector_dbs: bool = True

use_bm25_db: bool = False

llm_reranking: bool = False

llm_reranking_sample_size: int = 30

top_n_retrieval: int = 10

api_provider: str = "openai"

answering_model: str = "gpt-4o-mini-2024-07-18"

While testing configurations, I was surprised to find that table serialization—which I'd placed great hopes on—not only failed to improve the system but slightly decreased its effectiveness. Apparently, Docling parses tables from PDFs well enough, the retriever finds them effectively, and the LLM understands their structure sufficiently without extra assistance. And adding more text to the page merely reduces the signal-to-noise ratio.

I also prepared multiple configurations for the competition to quickly run various systems in all categories.

The final system performed excellently with both open-source and proprietary models: Llama 3.3 70b was only a couple of points behind OpenAI’s o3-mini. Even the small Llama 8b outperformed 80% of the participants in the overall ranking.

6. Conclusion

Ultimately, winning the RAG Challenge wasn’t about finding a single magical solution, but rather applying a systematic approach, thoughtfully combining and fine-tuning various methods, and deeply immersing myself in the task details. The key success factors were high-quality parsing, efficient retrieval, intelligent routing, and—most notably—LLM reranking and carefully crafted prompts, which enabled achieving excellent results even with compact models.

The main takeaway from this competition is simple: the magic of RAG lies in the details. The better you understand the task, the more precisely you can fine-tune each pipeline component, and the greater benefits you get even from the simplest techniques.

I’ve shared all the system code as open-source. It includes instructions on deploying the system yourself and running any stage of the pipeline.

Ilya is always open to interesting ideas, projects, and collaborations. Feel free to reach out to him via Telegram or LinkedIn

Published: March 25, 2025.

Next post in Ship with ChatGPT story: Evaluating LLM in business workloads